"The Solution is to Change Your Brain"

A conversation with a smartphone addict-turned screen time professional

In the fall of 2021, perhaps the hardest course to get into at the University of California, Berkeley—a school featuring a row of campus parking spots reserved for Nobel Laureates (nine of whom are active professors)—was a class focused on spending less time on one’s phone taught not by a Nobel Prize winner, nor, even, by a tenured professor, but by a 22-year-old undergraduate named Dino Ambrosi. The 30ish-capacity course—"INFO 98: Becoming Tech Intentional"—fielded hundreds of applicants, enough that Ambrosi was forced to shut down the class application before the end of registration. At the alma mater of Apple founder Steve Wozniak, a gaggle of Berkeley students, apparently, were just about ready to sling their iPhones into Strawberry Creek.

Ambrosi had found his calling. Upon graduating, he forwent an entry-level job and founded Project Reboot, a program (modeled after his Berkeley course) designed to reset the tech habits of a population caught in an “epidemic of social distraction.” Over the last three years, he’s launched curriculum-based courses in dozens of schools, delivered over a hundred presentations (including, in 2023, a TED Talk with over two million views), and is preparing to scale Project Reboot up to increase its presence in communities across the globe.

“I want every kid in the country to go through this program and to have clear space on their phone,” Ambrosi told me this week. “We have a right to technology that protects our attention and we need to get it out to everyone regardless of their socioeconomic status.”

Ambrosi and I studied in the same year at Berkeley, and since graduating I’ve tracked Project Reboot from afar as it increasingly aligned with my own interests. After I wrote a piece last month examining our guilt-laden, and increasingly responsibility-free, relationships with our devices, I reached out to Ambrosi to set up a meeting. The result was a really fruitful, nuanced, and compelling discussion about our societal screen time debacle, replete with a number of really useful tips and practical suggestions for entering a more mindful relationship with your device. Our conversation is below.

This conversation was lightly edited for length and clarity.

NS: I want to get into how you kicked off Project Reboot. Was there a specific moment or escalation that made you realize, oh my God, this is something I not only need to tackle personally for myself, but this is something I want to help others with? What sort of sparked that for you?

DA: There were a few key pivotal moments. There were a couple of points during college where I had major wakeup calls about my own use of technology. Both of those were prompted by viewing my screen time report and just being like, ‘Holy shit.’ I'm literally scrolling more than I'm studying, and I just had this burst of motivation to get my screen time down. It was something that I struggled with personally for the first two and a half years of college in a massive way. And then I got this opportunity to go to New York and that was like my reset button. I saw a lot of personal benefits from fully getting off everything for about a month and also building more structure into my life and starting to tap into the positive aspects of technology.

It struck me upon reflection just how profoundly changing my screen time had impacted my life. I went from scraping by in school to starting this internship with no role and getting promoted to the company's first product manager. I'd gotten in much better shape. I was running marathons and mentally just felt so much better. I could actually read books again. So I was just like, wow, my cognitive capacity, mental health, physical health, all of this has skyrocketed and it's all centered around how I changed my relationship with technology. Nobody helped me do that. I had to figure it out. I had a lot of shame—if somebody saw my screen time report, I would have been mortified because I thought it was just me. And so that was the moment, reflecting on that that I realized I could help other people with this and I bet there are other people struggling with it too.

So I decided to create a class at Berkeley, and I was really unsure if it was going to work at all. I didn’t know if we'd get people to sign up. We had to get 17 seats filled to run the class and I remember I made the application and I thought I'd be surprised if we got ten people to apply to this class. It's about using your phone less. How many college students are going to apply? Over the three semesters that I taught [the class], we got over 400 applications to the course from Berkeley students. And we had to shut the application early every time because we had more than hit capacity. So that was another thing where it was like, wow, this is bigger than I thought it was. I mean, the average student that came into my class was spending almost seven hours a day, non-productively, on their screen, as a Berkeley student. I saw students with screen time reports as high as 16 hours a day. So it really was teaching that class and having conversations with college students and seeing that nobody's getting help around us. And it just became crystal clear to me that I needed to be the one to build that.

NS: I was struck reading your bio that if you took the phone out of the equation, you would appear to be someone working through a substance abuse issue or a gambling addiction. You're specifically using the word ‘addict.’

At least in the sort of college-educated, computer job milieu, I think there’s a recognition that we’re on our phones too much and that there is something negative going on with our relationship with our phones, right? My frustration recently has been that the discourse has remained discourse. I sort of tiptoed around making this explicit point in my piece, but the acknowledgement that the phones are a problem is almost being used as an excuse, right? “I'm going to blame the algorithm. I'm going to blame Mark Zuckerberg. I'm going to blame Elon.” How do you think about balancing a perfectly legitimate case that, yes, Mark Zuckerberg could snap his fingers and reshape Instagram, for example, make the experience less addictive. On the one hand, yes, that is true. On the other hand, there is a level of personal responsibility, and you use words like insecure, guilt, shame. This hits at a super personal place. Do you think about how you're balancing the very personal impulses that this draws from versus these larger, more structural factors?

DA: There's a lot there to unpack. I know I say phone addiction, social media addiction. I say that because it quickly gets people to understand what it is that I'm really getting at, which is chronic, unintentional use of digital technology. I don't think we're actually addicted to our phone or to Instagram or to YouTube. I think we get addicted to escaping discomfort by seeking distraction and it's just the shortest path of distraction that we've ever had. Right? Even if you got rid of it. Like I got rid of YouTube and Instagram off my phone, and I still found ways to chronically distract myself through content consumption.

NS: My thing is ESPN.com, for whatever reason. And if it wasn’t that, it’d be something else.

DA: Exactly. I think there’s a balance to be had. It's important to recognize the fact that, yes, the algorithms and the incentives that social media are running on make the problem worse and they make it more addictive. And what they've really done is they've pushed social media from being social media to being entertainment. That's what it is now. I think it's important to see that as the problem it is, and to recognize that there is some culpability that the social media platforms have.

Because it alleviates some of the shame—it's helpful to see it's not just you being weak. It's you being manipulated, that is a component of it and it takes some of the blame and shame away, which I think is an important thing. To me, the epitome of doomscrolling is burying yourself in a rabbit hole, doing a deep dive, consuming content through whatever platform as a means of escaping the very uncomfortable confrontation with the fact that you've lost control over your behavior. So what I see is that when people realize they've become addicted to social media, the addiction actually usually gets worse before it gets better. Because that psychological discomfort of the recognition that you've lost your agency is so profoundly uncomfortable and the reason you got addicted to it in the first place is because it’s your means of escaping discomfort. So I think there's value in recognizing and kind of “boogeyman-ing” Zuckerberg and social media, because it alleviates some of the shame and guilt that people are running away from by turning to the platforms.

But from a first principle's perspective, as long as anyone on the planet can create content and upload it to the Internet and anyone else can consume that content, this will always be a problem. I loved your distinction between the algorithm and the apparatus. I completely agree with that. The algorithm is a compounding factor, but it's not the core problem. At the end of the day, it all comes down to changing the way that you respond to discomfort.

NS: And that's a lot—I mean, this is a job that you traditionally think about belonging to a therapist or a family member. We're in the realm of insecurity, guilt and shame. If people could figure out their discomfort with the world and these very, very deep things—death and illness, whatever we're shielding ourselves from—how do you approach that? Because you're taking this big, scary, nebulous mixture of these super primal fears and insecurities and shames, and you're funneling it through the lens of the phone. When you're sitting down with a group, is there a way to ease people into this, or do you go right for the big existential stuff?

DA: I don't call out the “you're not actually addicted to your phone, you’re avoiding discomfort by seeking distraction” thing until the end of the meditation. I call it turning to the digital pacifier. One of the first things I talk about in my presentation is how I fell into this doomed spiral of escapism through my phone. And the way that I first help people think about what to do and how to change their relationship to it is by focusing on the way in which they view the phone. I really don't think that there is a “right” relationship to have with social media or the Internet in general. I honestly think you can use social media for four hours a day and have a better relationship with it than someone spending 30 minutes on it.

It's not black and white. I think screen time is a decent proxy for the real objective, which is to be intentional. My goal when I work with students or talk to parents is adherence to informed intentions. That's the only thing that I'm really trying to do. I'm not a therapist, I'm not fully trying to change how you respond to stress and anxiousness. This isn't a drug and alcohol class. Fundamentally, the objective of what we're trying to do is get you to build a relationship with your phone where you know how you want to use it and you're following through on that. And what I've tried to do is just boil down this very big nebulous question to two really simple core ideas from which people can create their own intentions.

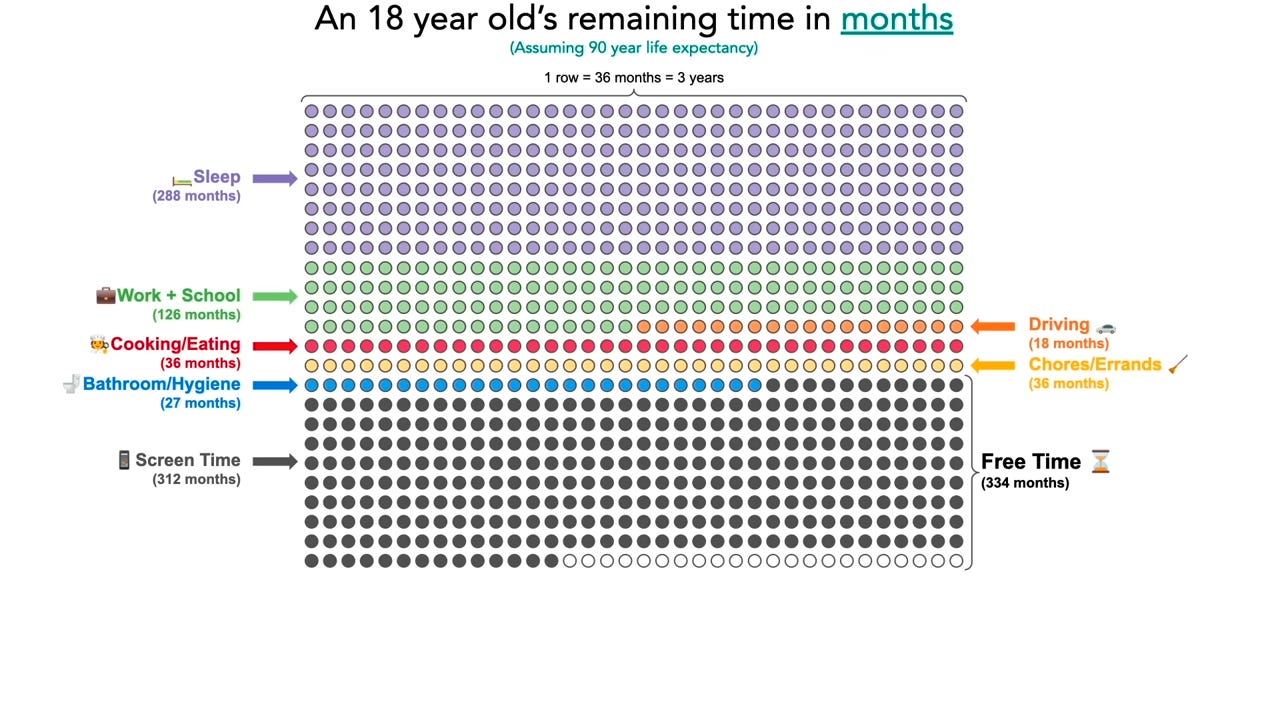

The first is that you just have to recognize that social media is not actually free. You're just paying for it with your time. So the only reason it's not charging you money is because you're not the customer, you're the product, and it's profiting off the time that you're spending. So recognize that your time is super valuable. That's why I have that visualization of how many months an 18-year-old has left.

NS: It’s in your TED Talk. You begin with this incredible demonstration. You're speaking to a group of high school kids, and you show them a big set of bubbles which represent every month they have left in their life if they live to 90. And then you fill in the bubbles with how they're going to be spending their time: sleep, chores, work, all these different things. You leave them with the third or so free open bubbles left after all those tasks. Then you ask this very fundamental, existential question: how are you going to spend this time? You show that if they continue their screen time use, something like eighty or ninety percent of that of that free time is used up. You can hear an audible gasp in the room, as these kids are realizing, “Holy shit.”

This is why I asked the last question, because if you're 18 years old and you're thinking about what your life is going to be like at 90, you inherently are getting into some pretty heady, existential territory right off the bat. It’s the first thing you do in that video.

DA: It’s the first thing I do in all my talks.

NS: So you are leaning on this existential thing. And then you bring it down to a more molecular level. Particularly with the high school kids, are you sensing that this balance is something that's working? Is this something they're receptive to?

DA: I've done this talk over a hundred times at high schools now. So I've been able to go through a lot of iterations and you can see when things are clicking or when they're not. And there's a lot of initial hesitancies and resistances that I've learned I need to overcome. I’ve noticed that when I do that graph, there's two reactions. Some of them are terrified by it, and you can see the shock in their eyes. Those are the kids that know they have a bad relationship with it. And they see themselves in that and it scares the shit out of them.

The other kids look at it and think, okay, that's wild, but it doesn't apply to me because I'm not spending eight hours and 30 minutes a day on my phone. They're frustrated about their parents putting restrictions on their phones, and they feel like it's a very condescending, accusatory, belittling conversation.

When it comes to giving them advice, it's being non-prescriptive and non-judgmental. Your time is valuable. That's what that first graph represents. You're paying for social media with your time. Just make sure you're getting a good deal. Figure out what value it’s adding to your life. And I think it's really important to acknowledge there's still a lot of value there. I still use Instagram and YouTube every day and I genuinely believe that they are net positives to my life. So I'm not saying that we need to get rid of them or that the optimal screen time is zero. Again, figure out what value it adds to your life and how much of your time that's worth.

NS: I’ve noticed that you don’t demonize the phone. You specifically mentioned you use Instagram, YouTube, you're talking up the benefits of information on the internet. Is that both effective messaging and how you personally feel about the devices?

DA: Yes. I don't want that to soften the strong critique I have of the way that phones have changed society. I think for most people, it has been a net negative. I just think it has the potential to be a net positive.

NS: So you still think that within this digital context, there's a world in which society as a whole can have a positive relationship with our devices?

DA: 100%. I've seen it. I had kids in my class at Berkeley go from seven and a half hours of nonproductive screen time per day down to an hour and a half, and sustain that for long periods of time. Yeah, you can change it. I mean, I've done it for myself. I'm not perfect about it. I still fall into negative behavior with it. But 100% percent yes, it's possible to develop agency and autonomy and how you use the Internet, even with the platforms having the negative incentives that they do. You can't will your way to it. You can't just set the intention and expect it to happen. You actually have to make internal changes and external changes.

NS: Right, so let’s get into what some of these changes are, so we can move away from this more theoretical conversation into a more practical one. Let’s actually get into the prescriptive stuff here.

DA: Okay. So, there's four keys to having a healthy relationship with technology. There's your intentions—which we just talked about—your environment, your habits, and your mindset.

With your environment, there's three types of changes you can make. There are physical environment changes, digital environment changes and social environment changes. Physical environment changes, super easy one: move the phone charger. If you could stay off of your phone for the last hour and the first hour of the day, the other 22 hours get a hell of a lot easier. I cannot wait until more studies officially validate this, but anecdotally from giving people recommendations and seeing how they respond, no phone, no addictive technology for the first 30 minutes to an hour of the day is one of the most effective things you can do. And then, obviously in the evening, if you can stay off your phone, you'll fall asleep faster, you'll get more sleep, you'll get a higher quality of sleep and you'll wake up actually feeling refreshed. So it has this huge, cyclical reinforcement effect. If you can get those two things right, everything else is so much easier.

Then there's digital environment changes. These are the easiest ones of all. There's a lot of helpful tools that are coming out—we're finally getting technology that leverages the same understanding about how our brains work that social media has been using to predict us, but in the opposite direction. And that is super powerful—everybody needs to be using them. Are you familiar with Clearspace?

NS: Explain it to me.

[Ambrosi at this point spends two minutes attempting to find his phone, which he’d left upstairs during our call, before returning to demonstrate]

DA: It does a couple things. First off, it makes you pause before going on a distracting app. I have to go through a delay where I’ll actually see how much screen time my friends had the prior day. And then I can give them little kudos and whatnot. It then asks me how long I want to go on the app for. So I can say, okay, I’m going to use Instagram for a maximum of ten minutes, and after those ten minutes are up it kicks me off the app. I have to go through another delay to start another session, and I’ve given myself a budget of three Instagram sessions per day. If I go past that, I lose my streak in the Clearspace app and my friend gets a text message from Clearspace saying that I broke my streak. That’s often the missing thing, the peer to peer social accountability. There’s other stuff. Notifications. Chrome extensions. They don't solve the underlying problem, but they'll certainly make it a lot easier for you to approach it.

Then there's social environment changes. This is a big part of why I talk to schools. The cultural norms that drive students' behavior are super powerful, right? So if it's cool to chronically doom scroll, you're gonna chronically doom scroll. If it's expected that you respond to Snapchats within five minutes, otherwise it means that you don't like the person or if you break your 500 day streak, that signifies the ending of your relationship, you're chronically going to be on Snapchat, right? So we actually have to have a cultural shift around how we use it. And I think we're starting to see that happen, this shift towards in-person genuine social connection is becoming more sought-after. There's run clubs starting. The students at Berkeley now teaching my class are organizing phone-free social events. It's starting to become in-vogue to unplug. So I think we can see those norms start to shift.

Then there's habit changes. Generally it boils down to prioritizing satisfaction over pleasure. “I've been studying for a while. It's been a long day. I need to use my phone to take a break because it'll make me feel better.” But it doesn't make you feel better. It's actually draining. It makes you feel better for a couple of moments just like eating a bunch of candy and then you come out on the other side and it's like you've taken an anti-nap. Now that you're feeling lower, you're going to re-engage in the same behavior to try to get back up because you have even less motivation now. So that's how you get caught in that loop. The other option is to do something that doesn't feel bad in the moment, but it's an active form of leisure. Reading a book or going for a walk or Facetiming a friend or playing an instrument or cooking or organizing your room. If that can become your default response to boredom, stress, anxiousness, loneliness, social awkwardness, whatever it is, it's actually an effective coping mechanism. So starting to retrain that is really at the core of it.

Then lastly there's some mindset stuff. There’s underlying beliefs we have that really influence our behavior. Prioritizing consistency over intensity in your behavior change and preparing yourself for setbacks, because there will be setbacks. I still go through setbacks. The difference is now I know how to rebound from them. And that's something that everybody can learn. It just takes time.

NS: You mentioned this earlier, where there is almost a sense of embarrassment here, even as someone who has identified this as a huge problem for myself, there’s an element of shame about how pedantic all of these things are. There's this weird mix of how this little thing in my pocket is combined with this deep, existential insecurity I feel while using it, and it can feel like the solutions should be these grand, lusty dreams of a mass revolution against the phones. And it's striking and somewhat disappointing for me, and I think probably for a lot of people, to realize that in the face of what feels like such a huge transformation in both our personal lives and society that the solution here is literally moving my phone charger to the next room, or downloading an app that's going to send a text to my friend, or give me 10 second delays. It totally makes sense that these solutions work, but it feels embarrassing that I should have to resort to these little tiny things, and it ties into the shame I feel when I look at my screen time. Is this something you're thinking about?

DA: Yeah, I think there's a middle ground there between those two. This stupid little trivial, “Move the phone charger, that’s the solution?” No, that's not the solution. It's an element of the solution. The solution is to change your brain. And that can happen. Your brain is always changing. When you first got a phone, it wasn't immediately a huge problem. It became a problem because that phone changed your brain over time and it's designed to do that. And the fact that it changed your brain means that your brain can change in the opposite direction. So the solution is to become more intentional, mindful, disciplined, and resilient. And that is a much grander objective than moving the phone charger.

There's this dissonance that people have—we identify as the narrating voice in our head, right? We identify as the version of ourselves that looks at that graph of our remaining months and sees 90% of our remaining free time taken up by this stupid little screen that's not adding value to our lives and we’re mortified by that idea, right? We often intuitively view that aspect of ourselves as all that there is, that inner narrator, that prefrontal cortex part of our brain. But we are more than that. Right? That conscious voice in our head rests upon this archaic, Paleolithic jumble of neural pathways that's not designed for the modern world, and we're not aware of it. But it drives our behavior more than the conscious part of our mind does, right? So literally recognizing that you, as in Nicky Shapiro, who’s reasoning about his own screen time—that’s not all you are. You're up against your own biology. And your biology is not designed to live with the smartphone in your pocket. So recognizing that it's a deeper issue and you have to have a more nuanced understanding of how your brain works and how you make decisions and what drives your actions. And it will benefit you not only in terms of your screen time, but in terms of your entire life.

Great interview about an interesting subject.